Day of the Church Year: 20th Sunday after Pentecost

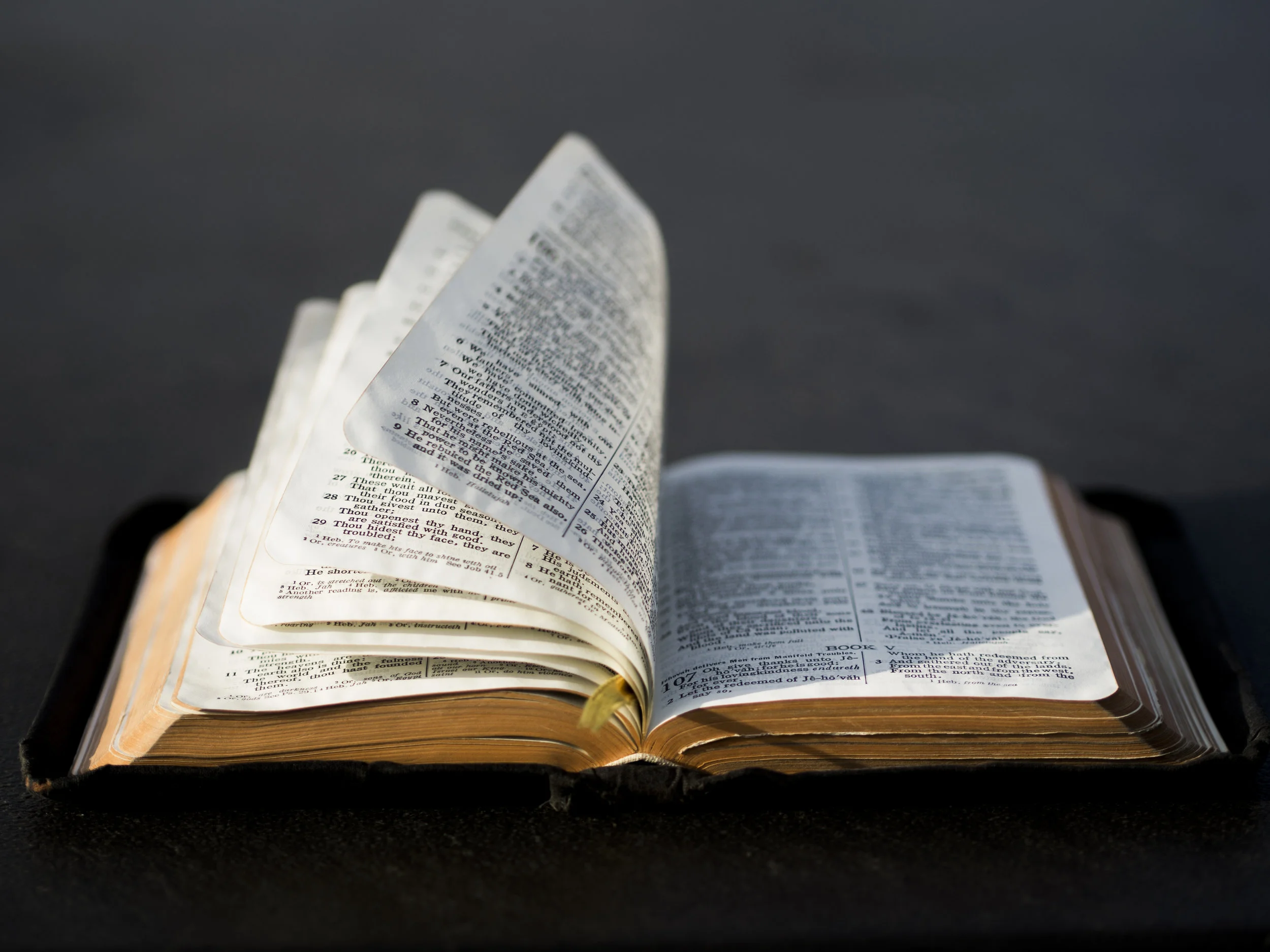

Scripture Passage: Mark 10:17-31

Jesus loves the rich man. The gospel writer Mark tells us so. Jesus does not condemn him. He does not blame him. Jesus does not condemn the rich man for being rich. Jesus does not blame the rich man for any reason. Jesus loves the rich man. Of course he does. When the rich man asks Jesus what he must do to inherit eternal life, Jesus speaks not in moral terms but in practical ones. Jesus tells him to sell what he owns and give the money to the poor and then to come, follow him. The rich man is shocked and grieves. The rich man grieves even though he is looking for life, and here, Jesus describes a way of living that brings life, even eternal life. But the rich man doesn’t want to hear that way. He wants a different way, perhaps an easier way.

Generations of Jesus-followers have also looked for a different way. We have assumed that Jesus does not mean what he says. We assume this is one of the places where Jesus is speaking in hyperbole or parable. Later, when Jesus says: “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God,” he indeed speaks in hyperbole. But not when he invites the rich man to sell what he owns, give the money to the poor, and come, follow him. Still, we wonder: does Jesus really mean it—for the rich man to sell what he owns and give the money to the poor?

Generations of biblical scholars have tried to find the loopholes in this episode, the mis-translations of the Greek, the cultural aspects of this passage we don’t understand. Some nonsense about a gate that “explains” how a camel can go through the eye of a needle; it’s an interpretation of the passage based on both the Greek and anthropological study. Questioning: does the Greek indicate the man is to sell all he owns or just some of what he owns?

We Jesus-followers and biblical scholars, we don’t want the complete giving away of our resources to be the way of eternal life. We want a different way. There are some Jesus followers who very intentionally give up everything, live in community with shared resources, and follow Jesus, people like Dorothy Day and Mother Teresa and even Shane Claiborne who founded The Simple Way and has lived in community for the past 15 years in Philadelphia. People do this but not a lot of people, and most of us are pretty sure we don’t want to join them. But does this mean we don’t inherit eternal life?

In today’s Jesus story, Jesus and the disciples discuss both eternal life and the kingdom of God which seem, from this passage, to be roughly equivalent to one another. In the beginning of the gospel of Mark, Jesus declares that the kingdom of God has come near when Jesus breaks on the scene, and Jesus continues to speak of the kingdom’s in-breaking throughout the gospel. Jesus’ declaration of the kingdom-come right then and there seems to indicate that the kingdom of God coming is not the same thing as an afterlife. Instead, the kingdom seems to show up wherever Jesus—and thus, God—is present. Only in the gospel of John does the phrase “eternal life” appear in anything but this particular story. Meaning, there is a story equivalent to today’s Mark story in both Matthew and Luke, but this one story is the only place the words “eternal life” appear in Matthew, Mark, and Luke. In John, Jesus speaks many times of eternal life, and in John, eternal life is not relegated to afterlife but starts now in our relationship with God and continues forever. If all of that biblical mumbo-jumbo didn’t make sense, I’ll just say this: I wonder if Jesus is talking about afterlife here. I’m not sure. I wonder if Jesus hears the rich man ask: What must I do to live in relationship with you? And Jesus responds: Let go of everything that gets in the way of you following me. And for the rich man, it is his riches.

What gets in your way of following Jesus?

Jesus invites us to let go of whatever that is.

It might be our riches. Most of us are not so different than the rich man, especially when we consider our socio-economic place on a global scale. Maybe Jesus’ invitation is one of monetary generosity or a simpler lifestyle. Our fear of social ridicule may stop us from following Jesus; I, for one, definitely avoid answering the question: What do you do? Based on where I am and who asks me. We might fear change in our lives; maybe we’re comfortable the way life is and don’t want our boats rocked. We might just be doing other things besides following Jesus and don’t feel like we have the time to serve others, to live in community, to love people even if they may never love us back. I invite you to ask yourself what keeps you from following Jesus and to consider, actually, letting go of whatever it is.

The good news about giving up whatever gets in our way of following is that, when we do follow, we are not left destitute. We get our lives back. But our lives come back different. They’re better. Peter hears Jesus’ teaching and cries out: “Look, we have left everything and followed you.” And Jesus responds that all who follow him receive all they’ve given up back a hundredfold—and with persecutions, he adds. We get a life of love and joy back a hundredfold—with persecutions because, of course, this radical Jesus-following life will always confound some. But when we give up what gets in our way, we receive back life, life abundant. Jesus issues the invitation to give up whatever stops us from following him because he, quite simply, loves us. Thanks be to God! Amen.